Back to the Amidah! The next blessing can be hard to pray.

וְלַמַּלְשִׁינִים אַל תְּהִי תִקְוָה וְכָל הָרִשְׁעָה כְּרֶֽגַע תֹּאבֵד וְכָל אֹיְבֶֽיךָ מְהֵרָה יִכָּרֵֽתוּ וְהַזֵּדִים מְהֵרָה תְעַקֵּר וּתְשַׁבֵּר וּתְמַגֵּר וְתַכְנִֽיעַ בִּמְהֵרָה בְיָמֵֽינוּ: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְ’הֹוָה שׁוֹבֵר אֹיְ֒בִים וּמַכְנִֽיעַ זֵדִים:

U’lemalshinim al tehi tikva, u’khol harisha k’rega toved. V’khol oyvekha mehera yikaretu. V’ha’zedim mehera te’aker. u’teshaber u’temager, v’takhnia bim’hera ve’yamenu. Barukh Atah Adonay, shover oyevim umachnia zedim. “May the informers lose hope. May all wickedness perish in an instant. May all Your enemies be cut off and may You uproot, destroy, devastate and subdue the wicked speedily in our days. Blessed are You, King who destroys enemies and subdues the wicked.”

This text of this blessing has varied more than any other in the Amidah, unsurprisingly, since gentile censors were often unhappy with what they found Jews praying. Various versions invoked curses on meshummadim/“apostates” and minim/”heretics,” instead of or along with “informers;” those terms are found in the earliest siddur, by the 9th c. R. Amram Gaon. Some siddurim call for the destruction of the “enemies of your people,” or “our enemies” instead of “Your – i.e. God’s – enemies,” and on “evil doers” or the “evil kingdom” instead of the abstract “Evil.”

Who were the original objects of these curses? It’s not really possible to say. The early Sages lived during ideological and sectarian rivalries, and numerous rabbinic texts display anxiety about heretics. Were Gnostics or some other forgotten ideology the object of the earliest versions? I’m unqualified to answer that historical question. But over the centuries, Jews typically thought this prayer was aimed at the early Jewish-Christians, whom they considered faithless apostates. How do you like this version from the Cairo Geniza? “May apostates lose hope, unless they return to Your Torah, and may Christians and heretics be destroyed in an instant. May they be blotted out from the Book of Life and not be inscribed with the righteous [Netiv Binah 1.283].” Such a prayer must not have won them friends among gentiles, and – I hope needless to say – we should not have such an intention in mind today.

Personally, I find it difficult to invoke divine curses on anyone. Once a year, on Passover, I don’t mind saying “Pour out Your wrath on nations who do not know You.” After the Shoah, it seems precious to deny that nations sometimes deserve divine wrath. But three times every day? That’s just not good for my neshama, or anyone’s. I recall davvening once in Efrat, in the West Bank, during the First Intifada of 1989, and hearing the prayer leader intone with passionate intensity: “may You UPROOT … DESTROY … DEVASTATE the ENEMIES OF YOUR PEOPLE.” It was awful.

Over the centuries, dating back to the Talmud itself, Jews contended with this problematic prayer through apologetic explanations. As far as I am concerned, there is nothing wrong with that – we can even be proud of it. We all inherit a sacred but imperfect tradition and must shape its message and meaning for our age.

To enable me to davven this paragraph with a full heart, I stress a few textual and contextual elements.

First, I never pray against my, our or Your people’s enemies. Only against Your enemies, God. There are such forces in the world, and they must be opposed. That is the meaning, to me, of the command to remember Amalek. Indeed, the 18th Rabbi Yonatan Eybeschutz said that davvening this paragraph of the Amidah fulfilled this mitzvah [Yaarot Devash 1:1].

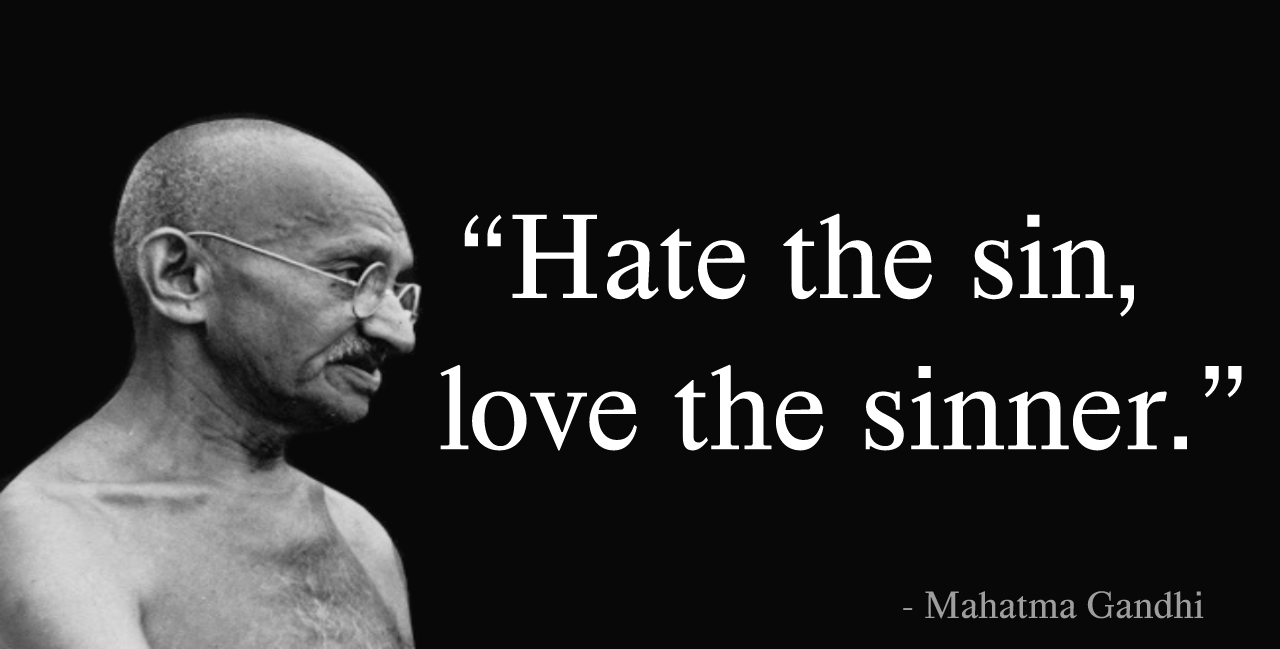

I never pray against “evil kingdoms” or “evil doers.” Only against Evil, which is real. I recall the Talmudic tale [Berakhot 10a] in which Rabbi Meir prays that local bullies should die, until he is corrected by his wise wife, Bruriah, citing Psalms 104:35: “May sins cease from the earth, and there will be no more wicked people.” She expounds that the Psalm does not say “sinners” should cease, but rather “sins.” Without sins, even your enemies cease to be wicked. Don’t pray that they die. Pray that they change.

Finally, I turn to the Talmudic tale [Berakhot 28b-29a] about this prayer’s composition. While this is surely legendary, not historical fact, it is rabbinic Judaism’s canonical story about the prayer, and influenced millions of davvening Jews for 15 centuries. And still does.

When the Amidah text was nearly finalized, Rabban Gamliel called for someone to compose a blessing against heretics. Shmuel HaKattan, “Samuel the Humble,” volunteered. But the prayer didn’t take. (Perhaps it was not intended for daily recitation, only for the rare moment.) A year later, by the time the same Humble Sam was called upon to repeat it, he forgot the words. He hesitated for a long while, the community waiting anxiously with him, until it came back to him. I take this tale to indicate that Shmuel was not eager; cursing even the deserving evil was an unpleasant duty.

It takes a uniquely gentle soul to take on the morally risky job of cursing evil. The haughty Rabban Gamliel or the stubborn R. Eliezer would have been disastrous. Only Samuel HaKattan – whose personal motto was “do not rejoice at your enemy’s downfall” [Pirkei Avot 4.19, Proverbs 24.17], who was eulogized as “the humble and pious, student of Hillel the Elder,” who was considered worthy of prophecy if only his generation were better [Sotah 48b] – could pull it off with the proper intention. This prayer could only come from a rare soul, capable of confronting evil without himself becoming cruel or succumbing to hatred.

Davvening the blessing against heretics is spiritually risky business. I advise us all to “handle with care.” Say it dutifully but reluctantly. Don’t let it poison your tender heart. May we all be students of Samuel the Humble.