א’להי אברהם א’להי יצחק וא’להי יעקב … א’להי שרה א’להי רבקה א’להי רחל וא’להי לאה/God of Abraham, God of Isaac and God of Jacob, God of Sarah, God of Rebecca, God of Rachel and God of Leah.

The initial blessing [“Avot”] of the Amidah invokes “the merit of our ancestors” by citing Exodus 3.6, God’s address to Moses at the burning bush, in which the Divine reveals itself as “God of Abraham … etc.” In a previous Tefillah Tuesday post, I suggested that the allusion should help worshippers feel that they, like Moses, are called to a divine mission, that their eyes be opened to see wonders, that they stand on holy ground.

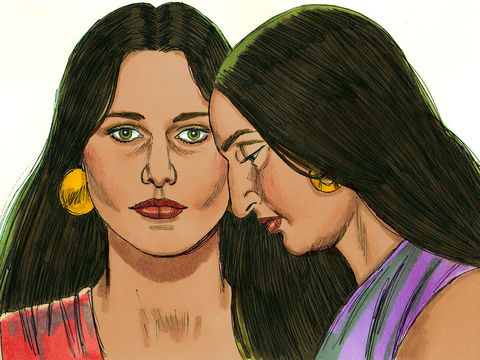

Today I want to address – all too briefly, for it is a complex topic – the widespread practice among liberal communities of adding the biblical matriarchs to the list of our venerated ancestors.

There are plenty of valid, coherent reasons for leaving the first blessing of the Amidah alone. Simple Halakhic formalism could end the conversation: you’re not supposed to deviate from “the formulae of prayer which the Sages created [Berakhot 40b].” For those who care more about tradition than law, this phrasing was uniform across all versions of all prayer books, across the entire Jewish people in all their homelands, from Poland to Persia to Tunisia, from the Talmud [Pesachim 117b] until about 1975. Continuity counts for a lot. So, I think it is legitimate for even strong feminists to decline to tinker with a passage built on a Torah quotation, which Jews have held in common for so long.

But that’s not my position. I add the matriarchs in the body of the first blessing.

I respectfully disagree with traditionalists, even heterodox ones, who object that the simple meaning of our scriptures is that the patriarchs, not matriarchs, were God’s true covenantal partners. While that does describe the Tanakh accurately, it poses its own question: why? The clear answer is that ancient culture focused on males and considered females junior partners. Do we want to perpetuate that?

When I davven today, I feel called to expand our sense of covenantal history to venerate those whose leadership, even in their own times, came from the sides, not the center. I try to remember that formal authority – which comes with official titles – is not the same as power and influence, which are exercised in multiple ways. Anyone reading the stories of Rebecca and Isaac knows that the Torah treats our mother as a much more consequential person than our ancient father, whatever social hierarchies were in play.

There are also ways to respond to formal Halakhic objections. The great modern Orthodox sage R. Daniel Sperber [On Changes in Jewish Liturgy, especially p. 59 and p. 111], who argues that what is prohibited is deviating in structure from accepted formats, not minor adjustments in phrasing that still utilize the same formats. Adding matriarchs’ names to the list of sacred ancestors is “completely permissible,” he says, as it conforms to the formula, if not to the exact wording. (This is a most cogent reading of Maimonides, Laws of Prayer 1.5-6. R. Joel Rembaum also made this argument for the Conservative Law Committee in 1990.)

When I daven the first central paragraph of the Amidah, I try to think about the characteristic qualities and narrative about each biblical ancestor:

· Sarah, bravely enduring capture in Pharoah’s harem.

· Isaac, symbol of strength and self-sacrifice.

· Rebecca, wise and full of foresight.

· Jacob, wrestling with himself, his past and future.

· Rachel, avatar of passionate, romantic love.

· Leah, unloved but unbowed, still grateful to God, mother of most of Israel.

You’ll notice I omitted one name from that list: Abraham. All our ancestors serve Jews as worthy models. But the Bible and subsequent Jewish tradition treat Abraham as being unique, “God’s dear friend [Isaiah 41.8].” Abraham is the one who left his land, his birthplace, his family, to begin the journey we still walk today.

Based on the primal promise to Abraham of היה ברכה/heh’yeh berakha, “you shall be a blessing” [Genesis 12.3], the Talmud [Pesachim 117b] records that while we mention all three patriarchs in our first Amidah blessing, we seal it with reference to Abraham alone: “Blessed are You … מגן אברהם/Magen Avraham, Shield of Abraham.” That’s no slight to Sarah, and not at all androcentric, since Isaac and Jacob are equally shaded. For this reason, I prefer to leave the summation of the blessing intact. But I think it is generally too demanding to ask English-speaking congregations to deviate from what’s printed in the siddur, like our Conservative Lev Shalem. For that reason, when davvening in public, I conclude the blessing the way our prayer book does, by adding the ופוקד שרה/u’foked Sarah, “who remembers Sarah.”