Jewish prayer is simultaneously intensely private and richly public.

Wonderful davvening can happen by yourself. One of the major Hebrew words for meditation is hitbodedut, or “cultivating aloneness.” Even when standing in a crowded shul, you need some sense of solitude to filter out distractions, master your stream of consciousness (not easy) and reach deep within your soul.

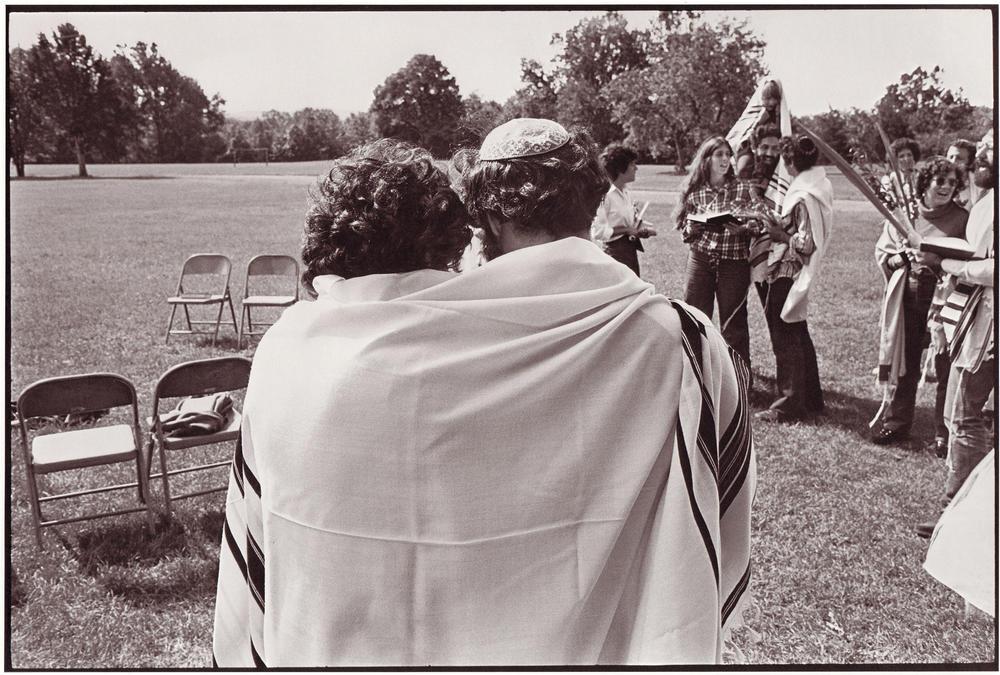

At the same time, Judaism has always favored tefillah betzibbur, prayer in public. Only a minyan of 10 can say the full liturgy, including devarim shebikedushah, or “matters of holiness,” like read the Torah ritually, repeat the Amidah or say Kaddish. With a minyan present, the whole nation is symbolically manifest, satisfying the divine commandment [Leviticus 22.32]: “I will be sanctified amidst the children of Israel.” Without that binding critical mass, we’re a straggling handful of individuals.

So let’s not prize hitbodedut too much. Being with other worshipers can enhance prayerful spirituality in several ways, from communal singing to helping you keep focus and rhythm, to reminding you that worship is not all about you.

Today I want to look at a 16th century teaching about how public prayer, at its best, binds davveners together in mutual love.

Our teacher is R. David ibn Zimra [“Radbaz”], who was expelled from Spain in 1492, at 12. He immigrated to the Land of Israel, later becoming Hakham Bashi (chief rabbi) in Egypt and one of the most important legal authorities of his age as well as a significant Kabbalist. The mystic R. Isaac Luria was his pupil in Cairo, although apparently in conventional rabbinic law, not necessarily in the mysteries.

Radbaz composed thousands of responsa, or written rulings. In this case [3.472] he guided a group of Iberian emigres who triggered social strife when they tried to secede from their local Tunisian community. Are they permitted to start a breakaway synagogue?

Besides addressing questions about the dissidents’ commitments to local Tzedakah funds, Radbaz speaks poetically about the spiritual impossibility of praying among people you don’t like, and, conversely, the advantage of praying among beloved friends and teachers. After surveying several Talmudic teachings about mental composure for prayer, he rules:

People should not pray in a place that disturbs them or at a time that disrupts their focus. When an individual or a group has resentment or hatred, anger or strife with the community, their prayers are unwanted, and it is forbidden to pray there. This is even more so when community members constantly provoke that person, or when the conflict is with the communal leaders. Were I not embarrassed to say something so bold, I would say it is even better to pray alone than among people one does not like.

Moreover, it is inappropriate to pray except where one’s heart desires. … For when people gaze on someone they like, their souls are aroused to complete focus, their consciousness expands, their heart rejoices and something like a spirit of prophecy rests upon them.

Furthermore, the books of wisdom [i.e. Kabbalah] say, when students focus on their teachers and devote their hearts to them, their souls bind with the teacher’s soul, and the students receive some of the teacher’s divine inspiration. Thus, the student receives an additional soul. And they call this “the secret of spiritual impregnation while both are alive.” … This is especially true if the teacher is also focused on the student. V’kara zeh el zeh, “and one calls to the other,” this one to bestow and that one to receive.”

This responsum was much beloved by 18th century Hasidim, who regularly seceded from local synagogues to pray in their own shtiblach or “little rooms,” hosting their mystical fellowships. They were glad to have the estimable Radbaz on their side when local misnagdim, “opponents,” tried to suppress them!

This teaching sketches out a theory of loving human fellowship as central to public prayer.

First, to explain the Kabbalistic allusion in that last paragraph: One version of the theory of reincarnation is that after death, diverse souls are recombined in new cocktails, and someone is born out of spirits of people who lived before and now will live again in the new person. This version is called ibbur or “impregnation,” because as a pregnant woman carries another person within her body, so too the reincarnated person carries some of other people within. In Rabdaz’s application, this interpenetration of soul within soul takes place – not after death – but in life, perhaps every day, as we gaze upon and learn from and absorb the essence of each other. It is “spiritual impregnation while we are both alive.”

Another tremendous element here is his allusion to Isaiah 6, familiar to all davveners from our Kedushah liturgy, in which the angels kara zeh el zeh, “call one to the other and proclaim Holy Holy Holy!” In this teaching Radbaz likens the prayers of teachers and students to that celestial chorus.

Finally take note of his audacious claim about the joy you feel upon looking at your friend in shul. Maybe you think sticking your nose in the prayer book will help you focus. Maybe you think looking around you is a distraction. Not so! Look at your friend and let the connection you have stimulate kavvanah so intensely that you reach an experience like prophecy, a direct communication from heaven.

This legal ruling about public prayer is ultimately a sanctification of friendship. If you love those praying beside you, reservoirs of generosity, beneficence, compassion and understanding can rise up within your heart and spill over.

These days, isolated in Covid, we are davvening together – if we’re lucky – only through our computers. Someday soon we’ll be together in the synagogue again. When that happens, take your nose out of the siddur, look around you, and say: I love you, I bless you, and feel myself blessed in turn, as my soul mingles with yours.