The next major section of the morning prayers, beloved to most regular daveners, is the פסוקי דזימרא [pesukei d’zimra], or the “verses of song.” Structurally, the core of this section are the final six chapters of the book of Psalms, from Ashrei, Psalm 145, to the end of Psalm 150, concluding with the crescendo כל הנשמה תהלל י’ה: “Let every breathing creature praise God!” Around that core, other material has accreted over time, including Exodus 15, [“the Song at the Sea”], Psalm 100, pastiches of different verses, and additional psalms added for Shabbat and holidays.

Regular daveners are accustomed to the rapid hum of prayer as we often recite these verses at breakneck speed. OK, admittedly, the prayer book is long. If we dawdle over every word, we’ll never get to work. But let me offer the comment by R. Yosef Karo, the author of the regnant Jewish law code, the Shulhan Arukh [OH 51.8]: “These songs should not be raced through, but said at a gentle pace.” I recommend picking a smaller number of psalms each day, or even a small number of isolated verses to linger over, and try to say them with devotion. Again from R. Karo [OH 1.4]: “Better is a little prayer said with concentrated intensity than many prayers said without it.” Amen to that.

While presumably the practice has old roots, pesukei d’zimra is not mentioned in the Talmud. A little textual archaeology indicates that the concluding blessing, Yishtabah, may be quite ancient [a topic for another note]. But we first hear of this formal, structured service in the prayer books of R. Amram Gaon and R. Saadia Gaon, in the 9th and 10th centuries. R. Saadia describes it, not as meeting an obligation, but as a gift: “Our nation volunteered to say these praises.” Beginning with praise may have seemed to them a way of buttering God up, currying favor before the petitionary prayer to follow [see Talmud Berakhot 32a]. This doesn’t work for me. But I do appreciate the idea that we wake our souls up and prepare for the official liturgy by exercising our “praise muscles.” The 18th and 19th century Hasidic masters described this as “praying to be able to pray.”

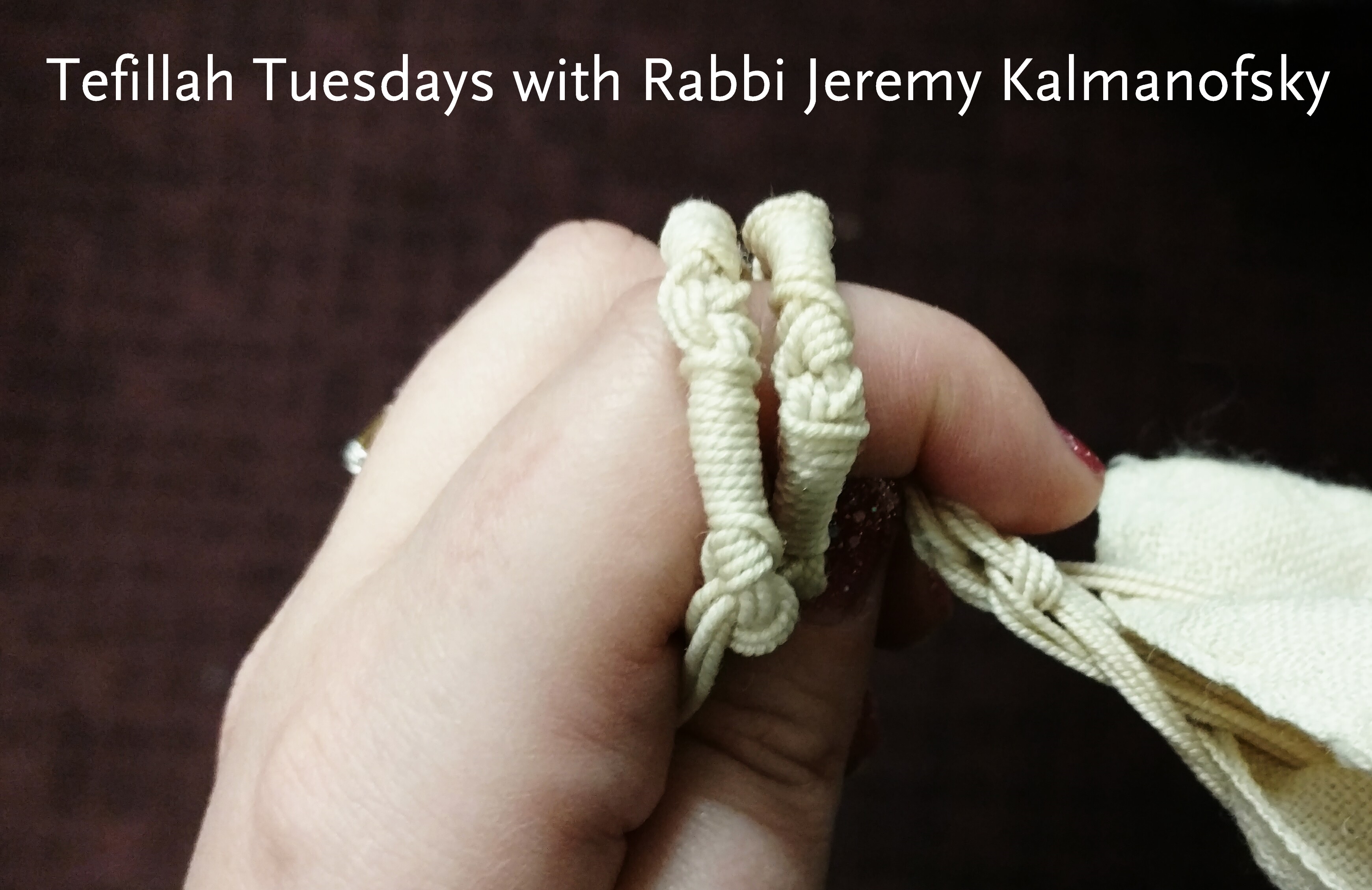

In today’s note, I want to make one note about ברוך שאמר [Barukh She’Amar], “Blessed is the One who spoke,” the introductory blessing beginning pesukei d’zimra. Prior to this text, many prayer books give a kabbalistic instruction, telling the worshipper to grasp the two front tzitzit of your tallit and recite a mystical intention: “Behold, I dedicate my mouth to thanking and praising my Creator, to unify the Blessed Holy One and Shekhina [i.e. male and female aspects of divinity], through the agency of the ultimately hidden.”

Why hold the tzitzit? Each tzitzit has eight strings and five knots, equaling 13; grasping two tzitzit makes 26, which the numerological equivalent of YHVH, the divine name. This is, in other words, a gesture of intimacy, and even more, a gesture asserting that God is, literally in your hands. The fancy word for this is theurgic, when you do this ritual act, the kabbalists would say, you affect God, unifying and manifesting God.

The mystical statement of intention reflects this nicely. God is the creator through language, the “One who spoke and the world existed.” [“Let there be light,” “Let the dry land appear,” “Let us make humanity.”] God’s creative force lies in language, the power to make meaning through words.

And this is precisely what we are about to do in prayer when we say “Barukh She’Amar.” With this small introductory meditation before this introductory prayer, we reflect that we resemble God in this way, possessing a capacity to change the world through our speech. And dedicate our mouths to praise and gratitude. Not to deception or flattery, not manipulation or exploitation, though our mouths can do all that quite well. We assert that God is a speaker of beauty, goodness, fullness and grace. Before we pray, we pray that we should use our power of speech the same.