Worship comes not only in words, but also in the choreographed dance of our bodies during prayer. Reciting Shema is no exception: Jews have engaged in a number of physical gestures to express the meaning of this passage.

What posture should one assume during Keriat Shema? The earliest rabbinic sages disputed. The school of Shammai favored a literal interpretation of the Shema’s prescription that we recite these words “בשכבך ובקומך, when you lie down and when you rise up.” So, the Mishna reports, they ruled that “in the evening each person should recline and recite and in the morning each person should stand up and recite” [Mishnah Berakhot 1.3, 9b-10a in the Talmud]. The school of Hillel, by contrast, took “when you lie down and when you rise” to refer to general times for Shema – morning and evening – not physical posture. Regarding how to hold your body, they stressed the words “ובלכתך בדרך, when you walk in the way” – meaning that one may recite Shema in “one’s one way.” You are free to “come as you are” in Shema: standing, sitting, walking, or laboring. As in most cases, the law followed the school of Hillel.

I would read this dispute a little poetically (perhaps more than its ancient participants would recognize), as expressing real differences of religious outlook. The school of Shammai seems to prescribe turning Shema into a choreographed ritual, a special moment of almost magical power. They call on us to stop whatever we are doing and exemplify God’s unity in a meditative dance, combining body and spirit, acting out a Shema that ends and begins our days, accompanying ourselves to sleep and energizing us to rise for a new morning. The Hillelites, on the other hand, seem to want Shema to be part of the flow of prosaic life, integrated into whatever a person is doing, not a distinct ritual which calls a halt to your other activities. Go ahead and say Shema when you are walking down the road or hammering nails or milking cows, or whatever is your job, for ה’ אחד, God is One, within your daily life, not outside of it. Obviously, this teaching dates from a time when our liturgy was still in formation, and people were not necessarily saying Shema in synagogues with minyanim, but in the course of their days and nights.

But this cannot quite be the end of the conversation, for a couple of pages later, the Talmud [Berakhot 13b] states that for some portion of Shema – perhaps just the first verse, or until the phrase בכל לבבך, “with all your heart,” or the entire first paragraph – the Shema should be said בעמידה, or “standing.” What gives? Didn’t Hillel rule that one could say Shema in any posture, standing, sitting, walking or working? Apparently, the somewhat later authorities in this passage [R. Yochanan and R. Natan bar Mar Ukva, 3rd century, as opposed to 1st c.] split the religious difference of the two approaches. While the rule may follow Hillel, it just didn’t sit right with these rabbis that reciting Shema demanded no special ritual focus, such that walking or working was fine for this act of worship. So they required people to “stand still” for a moment of the kind of religious focus on divine unity the school of Shammai would recognize. In this approach – as attested by virtually all Talmudic commentators, and even in the Jerusalem Talmud itself [4a] – the term עמידה or “standing” doesn’t mean that one has to rise to one’s feet. It means instead that one must stop moving for at least a moment to gain the requisite measure of focused intention we call proper כוונה, kavvanah.

Even this is not quite the end of the story, however. During the immediately post-Talmudic period – roughly 8th century – Halakhic history records that Palestinian Jews would literally stand on their feet when reciting Shema, while Mesopotamian Jews would sit. [See the Geonic work Differences between Jews of East and West, section 1.] Perhaps these Jews read the Talmudic term עמידה more literally, as demanding physical standing. Or perhaps they simply had a sense of ritual instinct, that “rising the occasion” fit the grandeur of Shema. In this, they would be the ancestors of classical Reform Jews, who instituted the practice of rising for Shema, to indicate its importance.

In Halakhic practice, however, we follow this middle position: One may recite Shema in any almost posture or during almost any motion, including riding on your horse [although not flat on your back or lying totally face down]. Still, it is considered best practice – though not absolutely required – to pause in place while saying the first verse, to gather your thoughts and focus a little more intensely.

For many of us today, who might not find ourselves in a synagogue each morning and evening, I find this teaching particularly helpful. OK, you might not have a prayer book handy, and you might not be able to stop whatever else you’re doing. But you can pause, stand still, breathe, look around you, recognize God’s unity and majesty and say the phrase Shema Israel Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad. Then continue what you were doing and continue with the rest of the Shema, or as much as you can manage or remember. It’s not a full synagogue service, sure. But remember: something is always better than nothing.

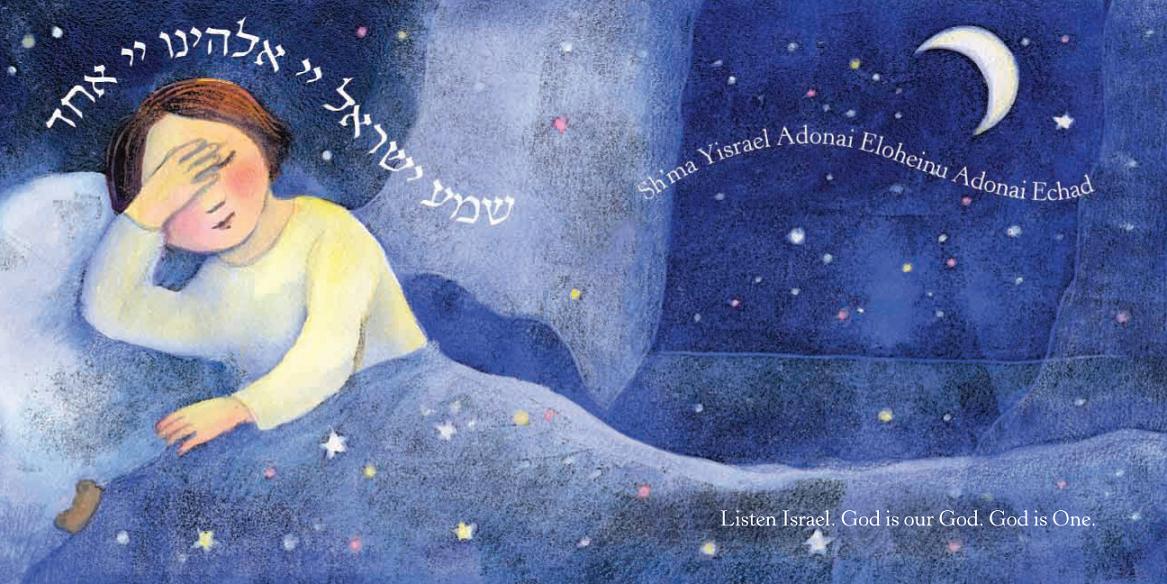

[image: The Bedtime Sh’ma, by Sarah Gershman (Author), Kristina Swarner (illustrator)]