After cursing the wicked in the 12th blessing, the Amidah proceeds to praise the saintly in the 13th [cf Megillah 17b].

Do you like that order? Perhaps it would better to set up a vision of the ideal first, and then curse our failures. But in truth, I think this order has its own logic. As Psalms 34 says: “Abandon evil and do good.” Often we must renounce bad patterns before we can attain virtue. Here is this blessing:

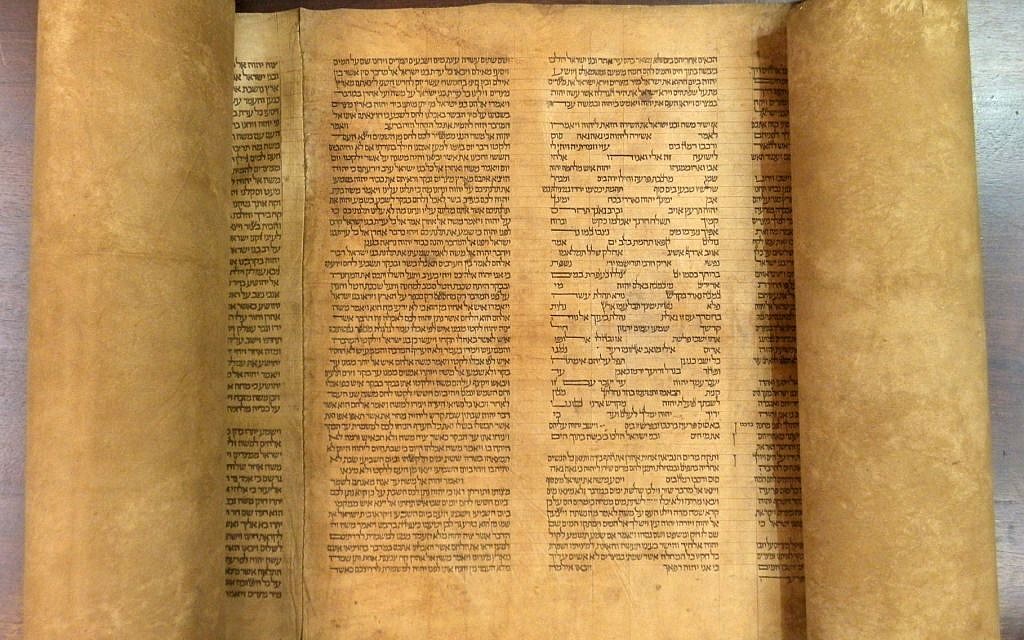

עַל־הַצַּדִּיקִים וְעַל־הַחֲסִידִים וְעַל־זִקְנֵי עַמְּ֒ךָ בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל וְעַל פְּלֵיטַת סוֹפְ֒רֵיהֶם וְעַל גֵּרֵי הַצֶּֽדֶק וְעָלֵֽינוּ יֶהֱמוּ רַחֲמֶֽיךָ יְ’הֹוָה אֱ’לֹהֵֽינוּ וְתֵן שָׂכָר טוֹב לְכָל הַבּוֹטְ֒חִים בְּשִׁמְךָ בֶּאֱמֶת וְשִׂים חֶלְקֵֽנוּ עִמָּהֶם לְעוֹלָם וְלֹא נֵבוֹשׁ כִּי בְךָ בָּטָֽחְנוּ:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְ’הֹוָה מִשְׁעָן וּמִבְטָח לַצַּדִּיקִים:

Al hatzadikkim, ve’al hahasidim ve’al ziknei amekha Beit Israel ve’al pleitat sofreihem ve’al gerei hatzedek ve’aleynu, yehemu na rahamekha Adonay Elohenu, ve’ten sakhar tov lekhol ha’bot’him be’shimkha be’emet, ve’sim helkeinu imahem, le’olam ve’lo nevosh, ki bekha batahnu. Barukh Atah Adonay, mish’an u’mivtah latzadikkim.

“Upon the righteous and the pious, upon the elders of Your people, the House of Israel, upon the remnant of their teachers, upon the genuine converts and upon us, may Your mercies be stirred, Lord our God, and grant abundant reward to all those who truly trust in Your name. Place our lot with theirs, and may we never be shamed, for we do trust in You. Blessed are You, Adonay, support and refuge for the righteous.”

Very interesting is the inclusion of sincere converts in the list of the saintly. Our tradition sometimes suspects converts and sometimes celebrates them. This blessing is clearly in the latter camp.

The phrase that often grabs my attention as I davven this blessing is פליטת סופריהם/pleitat sofreihem or the “remnant of their teachers.” As a rabbi with lots of friends in the business, this prayer for the well-being of Torah teachers feels close to home. May God reward me and my friends. Amen to that.

Especially emotionally vital, to me, is the term פליטה/pleitah or “remnant.” The classical term connotes those who escaped a crisis, like refugees. (The modern Hebrew word for refugee uses the same basic term.) Our Torah teachers do not ride in on white horses or drive Porsches. They’re limping back home, tattered and battered. The “remnant of the teachers” of the Jewish people are not Moses, not Hillel, not Rabbi Akiva, not Maimonides. But we are the students of the students of the students of the students of the greatest figures in the historical Jewish study house. And that is precious beyond words.

With the word pleitah, this blessing gives voice to that characteristic Jewish gripe about the “decline of generations.” Sure, we have Torah teachers, and we pray for their reward, but, honestly, they are a mere shadow of the golden days! Then again … we’ve been saying this line for a thousand years. Rashi davvened this phrase and he, too, must have considered himself among the sorry stragglers! So, as you davven, it’s OK to reminisce about Israel’s by-gone grandeur, but don’t sink so deep into it that you lose appreciation for what we still have. Be grateful for your own teachers. Reciting this blessing helps awaken my own gratitude to those I’ve learned from.

Invoking blessings upon the “remnants of our teachers” feels very vivid to me in at least one other way: the challenges of being a liberal rabbi. As a member of today’s pleitah, my colleagues and I try to bring alive for 21st century Jews an unimaginably old tradition – whose Biblical roots stretch to the Bronze age Near East, which was interpreted canonically by Rabbis in ancient Palestine and Mesopotamia, and which attained its mystical, philosophical and literary zeniths under medieval Christendom and Islam. That is a noble, sacred, always worthwhile task.

But we won’t always succeed. Torah is vastly deep and rich, but it can also be forbidding and sometimes inhospitable to any number of different people in our communities. Some of Jewish tradition deserves honest critique, and in very rare cases even needs to be rejected. And even when the tradition itself is not an obstacle, contemporary Jewish communities are not always the most fertile ground. It’s not easy to inspire generations who often lack the strong sense of ethnicity, spirituality and Hebrew knowledge that characterized many in previous eras. And then there is the problem that has beset liberal Jews as long as we have been receiving Western academic educations: is Jewish learning about “history” or “memory?” Do we seek Judaism wrapped in the poetry and myth and legend that our ancestral religion has bequeathed us? Or should self-respecting modern Jews set aside their fantasies in favor of the honest, sometimes brutal, truth? (And if you feel confident that honest history will ultimately enhance memory, you’re being too easy on yourself.)

There are no easy answers to these questions. But I feel blessed to be among the ragged remnant of teachers encouraging the Jewish people’s search for meaning in the Torah. We stragglers have not given up on the Torah, this eternal conversation among the Jewish people about how to live in God’s world. We are fully confident that the Torah is always pregnant with its own renewal.

May God bless the remnant of the teachers of Israel. Place our lot among them and let us not be ashamed, for we trust in You. וְשִׂים חֶלְקֵֽנוּ עִמָּהֶם לְעוֹלָם וְלֹא נֵבוֹשׁ כִּי בְךָ בָּטָֽחְנו.