ברוך כבוד ה’ ממקומו/ Barukh Kevod Adonai Mimekomo. “Blessed is the divine Glory, from Its place.”

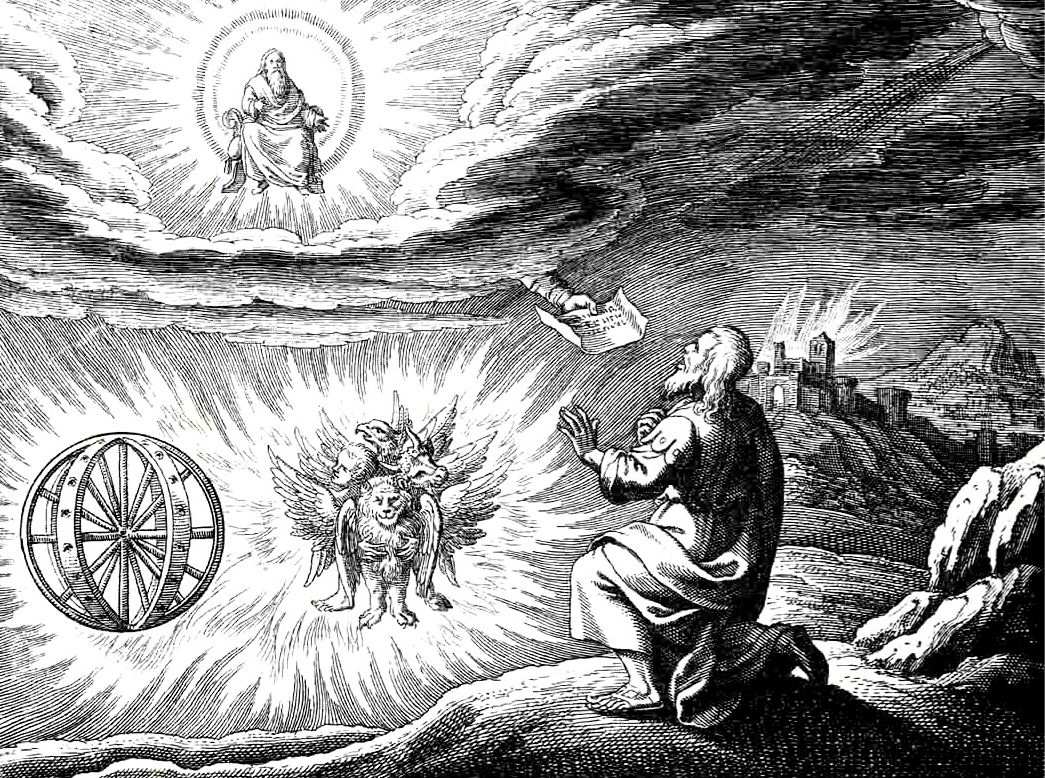

The second phrase in the call-and-response Kedushah comes from Ezekiel 3:12, drawn from the prophet’s vision of God riding a chariot drawn by four-faced glowing angels, with the most awesome visual and auditory pyrotechnics an ancient mind could have conjured. In today’s post I will share one mystical and one modern scholarly interpretation of the phrase, each of which might enhance your davvening.

After God delivers Ezekiel a message – which the prophet absorbs by eating the scroll he receives – he is caught in the tornado of the chariot’s motion and hears kol ra’ash gadol, “a tremendous roaring noise.” What is the content of that clamor? “ברוך כבוד ה’ ממקומו/ Barukh Kevod Adonai Mimekomo. “Blessed is the divine Glory, from Its place.”

Both the syntax and the semantics of this verse are difficult. Let’s begin with the peshat or semantic meaning of the puzzling reference to “Its place,” which in turn will lead us to the Holy Zohar’s [Spain, 13th century] brilliant mystical reading.

The religious import to Ezekiel lies in the fact that it takes place in exile. God was enthroned on Cherubim in the Holy of Holies. With the Temple destroyed, God is now banished, so to speak. But Ezekiel gets the revelation that those Cherubim now pull God’s chariot. The throne moves. The Blessed Glory has left Its [or “His”] place in Jerusalem to join the people in Babylon. [R. Itzhak Abarbanel, 15th century.]

For the Zohar, the word mekomo, “Its place,” or “His place,” hints at the impossibility of locating the Divine. Could anyone say where God belongs? The Zohar imagines that humans and angels are equally awestruck at God’s grandeur, but in different ways. People look up at the clouds and celestial lights and think God must be at home up there. Angels look down to earth and see the divine artistry and think God must belong down here. Each is only half right:

The Blessed Holy One is so lofty in glory. God is hidden and concealed, far beyond. There is no being in the world – never since the cosmos’ creation has there been any – who can grasp God’s wisdom or endure God’s presence, so hidden, concealed, lofty, beyond, beyond. All any being, on earth or in heaven, can do is to say: Blessed is the Divine Glory from Its place.

Those on earth look and say: God is in heaven, as it is written [Psalms 113]: Upon the heavens is God’s glory. Those in heaven say: God is on earth, as it says [Psalms 57]: God’s glory is in all the earth. So, together, all on high and all below say: Blessed is the Divine Glory from Its place, for the true Place cannot be known [Zohar 1.97a-b].

Davvening this phrase, I try to open my consciousness to God’s surpassing mysteriousness, belonging everywhere and nowhere, uncontainable, infinitely distant and incredibly close.

Now let’s move from the sublime to the precise. Ezekiel’s syntax is difficult. The Kedushah presumes that Barukh Kevod is what the chariot angels sing in the thunderous noise Ezekiel heard, paralleling the angelic praise Isaiah heard. But Ezekiel does not specify any being speaking. Conveying the traditional sense demands placing a colon between the description of the noise and the phrase itself, and inserting an otherwise only implicit speaker. “There was a great noise [which said]: Blessed is the Glory …” That’s all a lot of work.

Samuel David Luzatto [1800-1865, Italy], or “Shadal,” had an elegant alternative. Shadal was among the first Jews to venture interpreting the Tanakh through the prism of other ancient texts and Semitic languages and could see that Hebrew Bible developed over time. He did not like to propose emendations to our holy books – never to the Humash itself – but sometimes he had no choice.

Shadal noted that Ezekiel (especially chapter 10) typically refers to the chariot and cherubs ascending [רום]. Moreover, Ezekiel himself said the wings of the Cherubs were thunderously loud like a crashing waterfall or a marching army [1.24] as they flew upward. Shadal also knew that in ancient Hebrew script the letters kaf and mem look very similar. So he proposed changing a single letter to correct the error that crept in. Shadal wrote: “There is no doubt that Ezekiel did not write” the verse as we have it. But if you replace ברוך/blessed with ברום/ascended, not Barukh Kevod but B’rum Kevod Adonai Mimekomo, the verse makes perfect sense: “A wind lifted me up, and I heard behind me a tremendous roaring noise as the Divine Glory ascended [ברום not ברוך] from its place.” [Karnei Shomron 1851, ed. Kirchheim, p. 108.]

Can this academic tweak enhance your prayer? It has a plus and a minus. Unfortunately, knowing this does disrupt the parallel chorus of angels and people within Kedushah. On the other hand, it does evoke a sense of God in motion, a dynamism, traveling and visiting people along their journeys into exile, rather than locking God within a single shrine. And – if metaphor this works for you or evokes happy memories – it sounded like a rock concert. Imagine Springsteen or Beyonce overwhelming you through thundering amps, leaving your ears buzzing afterwards. Can you hear the clamor of the rock-and-roll angels’ wings and add that music to your davvening repertoire?