ראה נא בעניינו … רפאנו ה’ ונרפא /Re’eh na v’onyenu … refaenu Adonay ve’nay’rafeh. “Look upon our plight … heal us and we will be healed.”

To appreciate the subtle artistry of our prayer book, start with the Bible. In almost every line, the classical siddur quotes, alludes to, or rephrases a Bible passage.

Sometimes it gives a direct quotation. But more often the siddur paraphrases, altering a sacred text to emphasize some point or nuance. Why did the prayer book editors change this or that word? Why did they introduce a new idea? Or omit an old one? Why did they mash-up several verses?

In the seventh and eighth blessings of the Amidah – the petitions for ordinary, day-to-day salvation and for healing – we discover a characteristic maneuver of the prayer book poets: they transformed individual prayers, phrased in the singular, into communal ones, phrased in the plural. Bible characters spoke as individuals making personal pleas, but the prayer book composers built a communal liturgy, transforming prayers for me into prayers for us.

The blessing ga’al Israel begins re’eh na v’onyenu, or “see our plight.” That paraphrases Psalms 119.153: re’eh v’onyi, or “see my plight.” Riva rivenu, the blessing continues, “fight our battles.” This rephrases Lamentations 3.56: Ravta Adonay rivei nafshi, ga’alta hayyai. “Lord, You have fought my life’s battles, You have redeemed my life.”

The same pattern recurs in the petition for healing. Jeremiah 17:14 reads: “Heal me Lord, and I will be healed. Save me and I will be saved, for You are my praise.” That is exactly how the blessing reads in our siddur, except that each reference has been turned from a singular to a plural: heal us, save us, for You are our praise.

Jewish tefillah has individual elements, summoning us to “pour out our hearts like water,” and engage our personal anxieties and hopes.

But structurally and spiritually, davvening Jews pray communally. We pray for each other, not primarily for ourselves. Those who pray only for themselves are like people who, during battle, reinforce the doors of their homes, instead of repairing the city walls, said R. Judah HaLevi [Kuzari 3.19].

A particularly rich expression of this idea – citing the very blessings I mentioned – comes from Sefer Hasidim, a collection of spiritual teachings associated with the “Hasidei Ashkenaz,” German mystics and pietists of the 12th and 13th century (not to be confused with the Hasidic movement of the 18th century):

Some people pray and are answered, and others pray and are not answered. Prayers go unanswered because people do not take to heart the suffering and shame of their fellows. These prayers deserve to go unanswered, for people should always think: If I really cared about other people’s pain, I would pray for them. And it is written Love your fellow as yourself. Those who do not share the suffering of the righteous, do not deserve to have their prayers answered. This is why the Sages demanded reciting all prayers and pleas in the plural, such as heal us, and look upon our plight. As it is written: God will grant you mercy and have mercy upon you [Deut 13.18], meaning that when people show mercy to others, heaven has mercy upon them [cf. Shabbat 152b]. If we do not pray for others, we are no better than beasts, who do not care for their fellow creatures’ pain. [Sefer Hasidim, #553, Margaliot ed.]

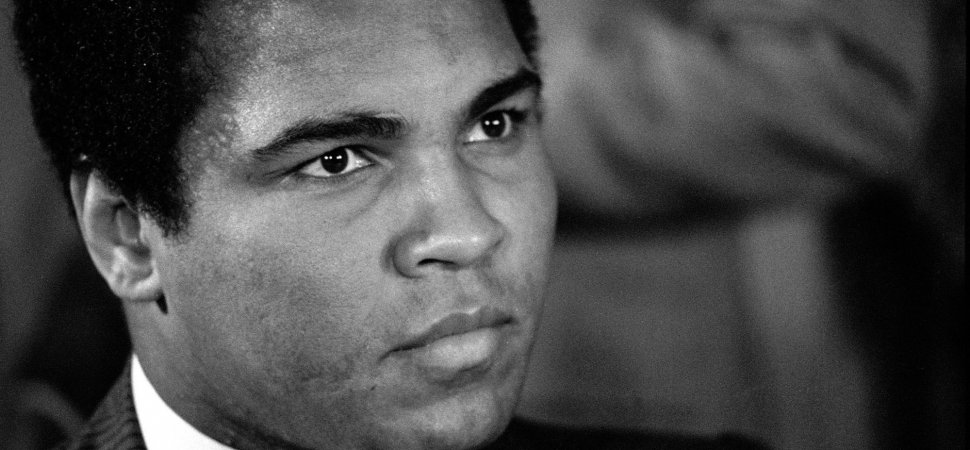

A fine teaching from a medieval Jew. Let’s match it to one by a great American poet, the champ, the greatest, my fellow citizen of Louisville, Kentucky, Muhammed Ali.

The champ – who, eloquent and thoughtful as he was, barely graduated high school, thanks only to some generous Ds – once gave a commencement address at Harvard University. When he concluded, someone from the crowd called out, “Champ, give us a poem!” He replied:

“Me? We.”